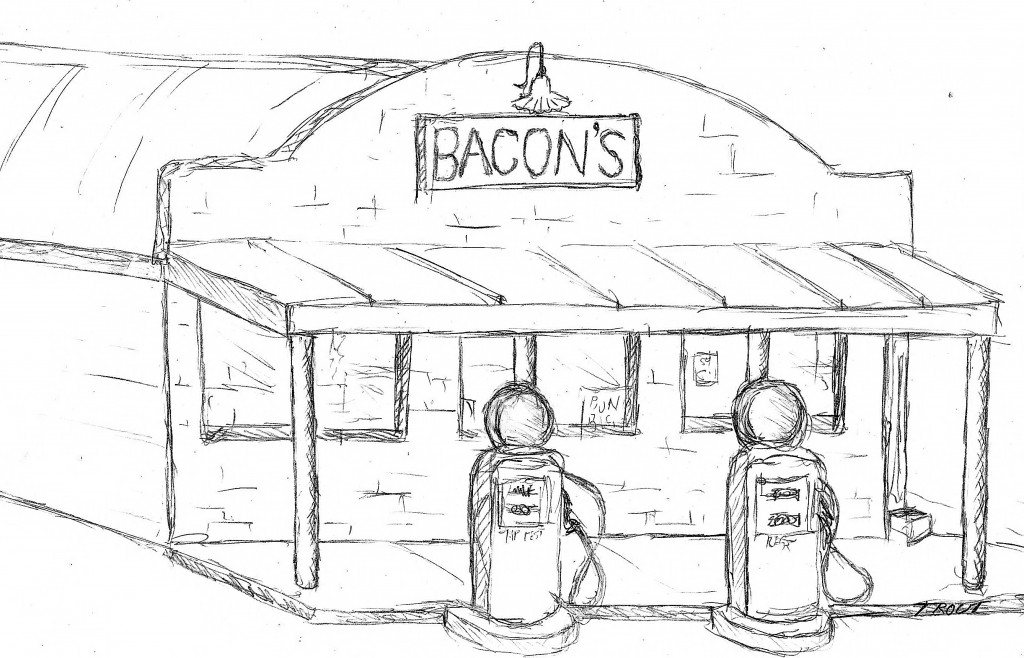

When I was a little boy, it was a big treat to run down to the corner store and buy a Three Musketeer bar and a bottle of Coca Cola. The store was a small, 3-aisle establishment called Bacon’s Market with a small canopy and two gasoline pumps in the front. Horace Bacon, the proprietor, wore a white apron splattered with flecks of blood as he often served as both butcher and cashier, running from the meat case in the back of the store to the register in the front. As horrifying as that sounds today, it was something of a necessity in a small town, and the townspeople were both mentally and physically immune to the practice. Besides, if you wanted to really take some chances with your health, you would eat at Beaner Lee’s down the street.

When I was a little boy, it was a big treat to run down to the corner store and buy a Three Musketeer bar and a bottle of Coca Cola. The store was a small, 3-aisle establishment called Bacon’s Market with a small canopy and two gasoline pumps in the front. Horace Bacon, the proprietor, wore a white apron splattered with flecks of blood as he often served as both butcher and cashier, running from the meat case in the back of the store to the register in the front. As horrifying as that sounds today, it was something of a necessity in a small town, and the townspeople were both mentally and physically immune to the practice. Besides, if you wanted to really take some chances with your health, you would eat at Beaner Lee’s down the street.

Food was relatively cheap despite the low wages in the early 1960’s. The Coke and chocolate bar were five cents apiece, something a young grade-school-er could afford even back then without asking his parents for a twenty. I never received an allowance, but cut lawns in the summer and coupled with my Grandmother’s gift of a nickel a week and soda bottle returns (one penny per bottle), I was a small town tycoon.

I never noticed it on the green-glassed Coke bottle, but when Horace Bacon stocked the new Royal Crown Cola, I bought my first RC, went out under the front canopy, sat against the front wall, and took a swig. I looked down at the bottle and spied these little white markings painted beneath the red and white “RC” symbol . . . “16 fl oz”

What the hell is a floz? I thought. I wasn’t a stupid kid, and I was pretty sure it meant “sixteen fluid ounces,” but with the lack of punctuation, how could it be? I ran back into the store and pulled a bottle of Coke from the big, red chest cooler. There was no paint on the Coke bottle, just embossed letters. The big words “Coca Cola” were clearly visible, but the volume was a little less prominent. That’s why a never noticed it! In small print under “Coca Cola” was “12 fl.oz.” Even the little periods were there. My third grade teacher, Mrs. Chambers, would be proud. A+ for Coke, something in a D- for Royal Crown. Who cared? The RC bottle was huge! Sixteen floz!

After I finished my giant RC, I thought about the abbreviation fl. oz. Using “fl.” for fluid made sense to me, but why “oz.” for ounce? There’s no “z” in ounce! The floodgates of my brain opened and other shortcuts flooded my head with no hope of stemming the tide. Why was a sixteen penny nail written as 16d ? What did A.M. and P.M. mean on the clock? And how about A.M. and F.M on the radio dial? These were mind-bending ideas to an eight-year-old, especially in the year of our Lord 1960 A.D. So I decided to quell my mental tidal wave with some answers, because as my mother taught me, an oz. of prevention is worth a lb. of cure.

It seems the word ounce was derived from a 14th century Latin word uncia, meaning one twelfth of a whole. Still no “z.” However, the abbreviation is the shortened form of onza, the Italian word for one twelfth. The Spanish word onza, which is uncredited for the “z” in oz., ironically, is one-sixteenth of a libre. Though it didn’t make a lot of sense to me, I found the “z.” I inadvertently found the origin of the abbreviation for pound, also.

“Lb.” was derived from the Latin libra, meaning “scales” or “balance.” Ancient Romans used the word for a unit of mass and, you guessed it, was divided into 12 uncia (ounces). Again, I didn’t understand how we got from “pound” to the Latin libra, but apparently lexicography was as wacky as the Navy.

The meaning of AM and FM on your radio wasn’t done the Navy way (the bigger the ship, the smaller the number). AM is short for amplitude modulation and FM for frequency modulation. Radio waves carry signals that we hear as sounds on a speaker by modulating, or changing, the wave.  As you can see on the animation on the right, FM signal waves are closer together and more even. The AM signal’s amplitude (height) varies, causing the signal to fade in and out at times. Lightning often interferes with the highest peaks creating the static in transmissions so well known to “parking” participants grooving to the car’s AM radio in the 50’s and 60’s. FM? Hey, put on your high heeled sneakers! No static at all!

As you can see on the animation on the right, FM signal waves are closer together and more even. The AM signal’s amplitude (height) varies, causing the signal to fade in and out at times. Lightning often interferes with the highest peaks creating the static in transmissions so well known to “parking” participants grooving to the car’s AM radio in the 50’s and 60’s. FM? Hey, put on your high heeled sneakers! No static at all!

Everyone opines on the symbol “d” used in sizing nails. Unfortunately, it’s not as romantic as some people believe, like how a store clerk would place so many pennies on one side of a scale and add nails to the other side. Once balanced, this determined the size and price of certain nails. The real skinny is this, the symbol d comes from the Latin denarius, which later became the French denier, or penny. During the 15th century, England sold nails by the “penny size,” which was the price of one hundred pennies of that size (the hundred was actually the “great hundred,” or 120 nails.). The United States adopted this designation of listing a nail’s length by its pennyweight, although most other nations converted nail measurements to decimals.

Before I close, a word about Beaner Lee mentioned earlier. Beaner’s was a very small eating establishment on High Street on the way out of town. Unfortunately for a number of human pathogens, the griddle was hot, and the rest of the food prepackaged in antique cellophane. An urban legend insists that two well-dressed lawyers were on the way to the State Prison down the road, when they stopped at Beaner’s for a bite to eat. It was a very hot day, and Beaner, slaving over the griddle all morning, came out the kitchen and greeted the young lawyers.

“Whadda ya have, boys!” Beaner bellowed in an unbuttoned short sleeve shirt.

“Well, could we have a couple of hamburgers?” they asked.

“Howda ya wan’em cooked?” Beaner said wiping his greasy hands on his sweaty chest.

“Medium.” was the first reply.

The second attorney looked at his friend, then at Beaner and said, “Just fry the piss out of mine!”

.